Category: Equity

Growth of electric vehicle infrastructure offers hope for repair and renewal

Shrika Madivanan, Digital Communications Intern and Justin Brightharp, Senior Program Manager

Updated January 4, 2024

Pursuing equitable solutions starts with acknowledging the legacies of discrimination in in southeastern energy and transportation systems. In 2023, SEEA created three new StoryMaps that take a look at how energy security and equity impact transportation in Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina. We used data from federal and state sources alongside stakeholder feedback that tell a story about how transportation systems impact Black and brown communities and low- to moderate-income communities.

Each StoryMap utilizes unique data and stakeholder engagement, but share a common narrative that recognizes the unequal distribution of the benefits of clean transportation, community inclusion in decision-making, and burdens of emissions. They also provide policy recommendations that support an equitable transition to zero emission transportation. The StoryMaps are a resource for decision-makers and other stakeholders to identify which communities have experienced the most negative impacts from the transportation system and how to pursue federal and state funding opportunities that reduce transportation emissions, economically support communities and improve local public health.

SEEA is committed to acknowledging the influence of historic racism within the energy sector and related industries such as healthcare, insurance, housing finance and transportation. Racial segregation has always been a part of our country’s transportation systems and these historical inequalities still impact energy efficiency and transportation equity today. SEEA is developing a set of maps that illustrates how transportation infrastructure places additional burdens on people of color, and how zero emission public transit, fleets, and personal vehicles can address these issues.

One of the most notable challenges in the system is an absence of charging systems in Black, Latino, low income and rural communities. The lack of accessible charging stations in minority communities today is the result of a long history of prioritizing white spaces. When Congress approved the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, they intended to ensure “speedy, safe transcontinental travel,” but in doing so they also displaced many Black households. Many Black neighborhoods were demolished to build the interstate highway system, which amplified existing inequities like racial segregation and poverty. The destruction of these vibrant communities made accessing basic needs such as housing and access to clean air a burden for those who lived there.

Black residents who were not displaced experienced ongoing discrimination because the newly built highways cut off minority neighborhoods from economic opportunity. Often excluded from white neighborhoods, they were pushed to find new housing in communities already segregated by race and class. This put Black communities at an even greater disadvantage when looking for quality housing, employment opportunities and public services.

Public transit also has a history of racial inequality. When streetcars were first introduced, they initially created opportunities for people of color, making travel throughout cities more convenient. Still, segregation remained commonplace through mechanisms like separation screens and assigned seats. Though these explicit tools used to perpetuate racism have since been outlawed, access to public transit is still stratified by race.

Many public transit systems today are built on the foundation of two different consumers, “choice” and “dependent” riders. These terms mask descriptions of white and Black people, concealing biases toward white riders. This bias appears in transit system design. Systems are built under the assumption that “choice riders” need accommodations such as new rail lines and more accessible routes because they have a choice, whereas “dependent riders” receive the bare minimum as they have no room to be selective. Transit systems take extra steps to build schedules, route structure and infrastructure centered around white people. This bias extends to electric vehicles (EVs). The EV sector is growing quickly, aided by consumer interest and an influx of federal funding. This time of growth and transition provides an opportunity to build a better system and not repeat the mistakes of the past.

While improvement is still needed, public transit has reduced emissions and provides affordable, necessary services. The use of zero-emission buses is one example of the transit system making strides to be more sustainable and accessible. The Southeast has the second largest percentage of zero-emission buses in the nation, just behind the western states. The transit agencies that serve Lexington, KY, Chattanooga, TN, and Orlando, FL are regional leaders in low and zero emission buses. Last month, the City of Orlando released its 2030 Electric Mobility Roadmap outlining the city’s vision for cleaner, more equitable mobility opportunities from public transit to EV adoption to multimodal options.

Accessible, clean transportation creates opportunity and improves the quality of life for all. In addition to increasing the number of locations of charging systems, increasing the different types of charging systems ensures charging is easy to access and affordable. State and federal incentives like rebates reduce the upfront cost to purchase a new or used EVs, removing an additional barrier to adoption.

There are multiple obstacles that impact widespread EV adoption in minority and low income communities. Charging infrastructure is not widely available yet and it’s estimated that 80% of EV charging occurs at home and work. If a driver’s home or place of work does not have charging stations, they will need to install a charger at home, which increases upfront costs. Most Americans buy used vehicles as opposed to new vehicles. However, used electric vehicles are harder to find at most used car dealerships. Although the majority of people in the U.S. and Southeast drive personal vehicles, many people rely on other forms of transportation such as motorcycles, bikes, and public transit. Improving fleet electrification – the transition of light-duty vehicles, trucks, and delivery trucks to electric vehicles – is essential to expanding accessibility and provides additional options for clean transportation.

Transitioning to more low and zero emission vehicles is critical to Black, Latino and low income communities adjacent to interstate highways and travel corridors. Black and Latino communities are disproportionately affected by air pollution, and the lack of electric vehicles and charging stations within these communities contributes to emissions levels. From 1990-2019, a hike in demand for travel resulted in an increase in CO2, methane, and N2O emissions from buses by 162% and from medium and heavy-duty trucks by 92.9%. Medium and heavy-duty vehicles, including buses, account for less than 10% of vehicles on the road but contribute more than 60% of NOx and PM emissions.

Prioritizing building charging infrastructure in Black, Latino, low income and rural communities will make EV adoption easier, more affordable, and inclusive of all people living in the Southeast. Improving the accessibility of charging infrastructure will give way to new economic growth locally and regionally. EV drivers have longer dwell times, up to 45 minutes, at charging stations compared to gas stations. This extended break encourages time at nearby businesses like restaurants or shopping. In the Southeast, the EV manufacturing sector is expected to add thousands of jobs and billions in revenue to states and municipalities.

SEEA uses resources like StoryMaps to engage with regional and national decision makers on how to make the transition to low-and-zero carbon emissions vehicles more affordable and accessible and move towards a more just transportation system. We plan on publishing a new StoryMap focused on transportation and equity soon. If you have questions about this work, contact Senior Manager, Justin Brightharp.

Map of the Month – December

Grace Parker

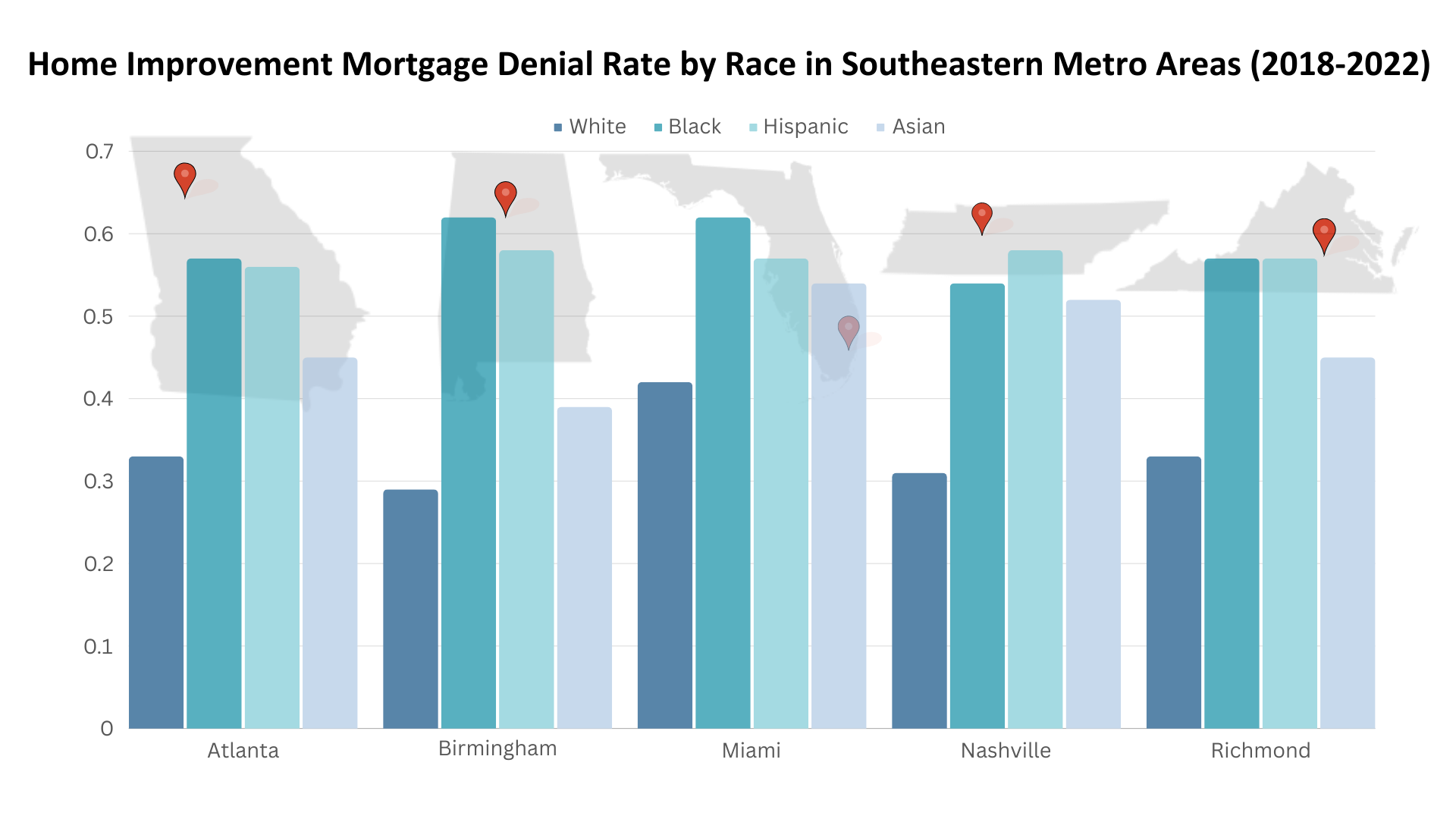

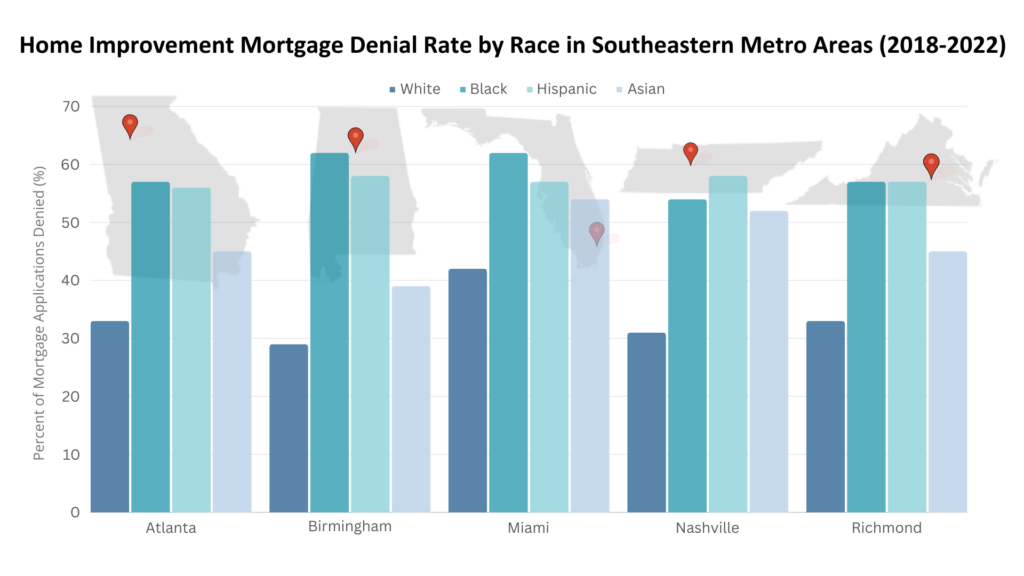

Source: Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, Home Mortgage Disclosure Act Dataset; Graph: SEEA

Following last month’s map that explored home purchase mortgage denial rates by race, this month’s map shows home improvement mortgage denial rates by race in five Southeast cities: Atlanta, Birmingham, Miami, Nashville, and Richmond. Like mortgage loans for home purchases, we found wide disparities between racial groups in their ability to access lending for home improvements. Using data collected by the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to ensure compliance with the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act, we discovered that the denial rate for home improvement loans in each city is highest for Black and Hispanic applicants, followed by Asian applicants, with white applicants experiencing the lowest rates. In Birmingham, the denial rate for Black applicants is twice that of white applicants.

In each of these cities, denial rates for home improvement mortgages are generally higher than those for home purchase mortgages. Home Mortgage Disclosure Act regulations consider home improvement loans as those that are “for the purpose, in whole or in part, of repairing, rehabilitating, remodeling, or improving a dwelling or the real property on which the dwelling is located.” This includes home improvement spending built into mortgages for home purchases or lines of credit opened for home improvement if the home itself is used as collateral on the loan.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Housing Survey, about a third of home improvements in the Southeast are for energy efficiency measures. Limited access to capital for home improvement hinders the ability of homeowners, particularly Black, Hispanic, and Asian homeowners, to make energy efficiency upgrades. This further contributes to racial disparities in energy costs and burdens and makes it more difficult for people of color to access healthy, efficient and affordable housing.

Map of the Month – November

Grace Parker

hover over the map to click through the slideshow

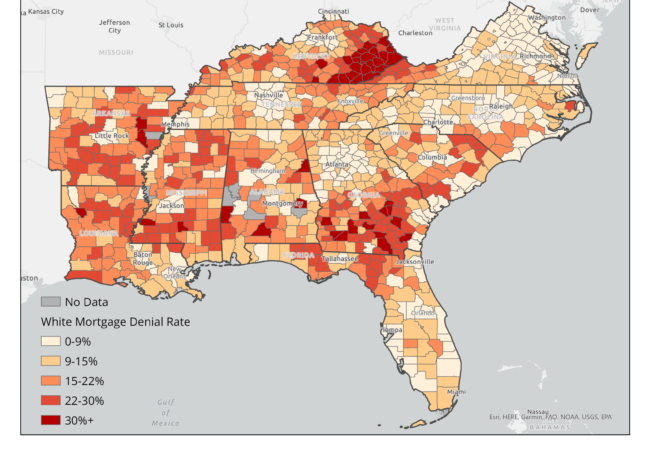

Source: Dynamic National Loan-Level Dataset, U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau; Maps: SEEA

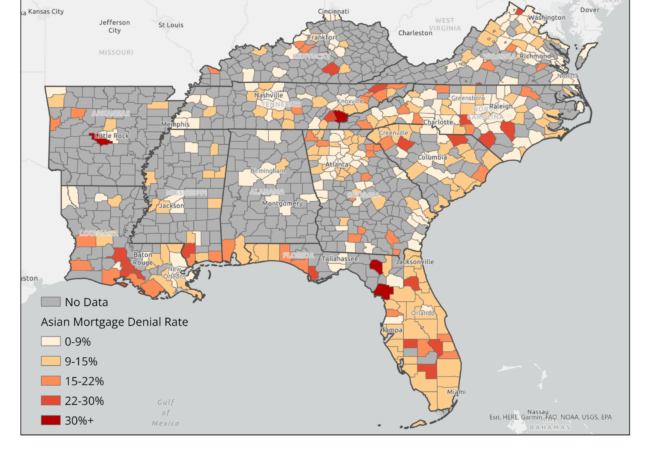

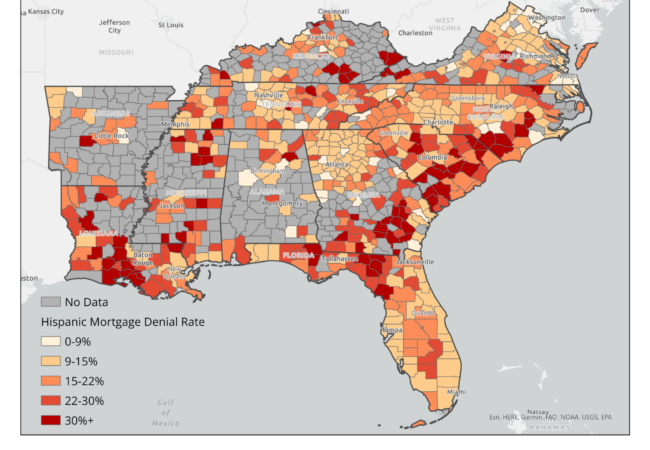

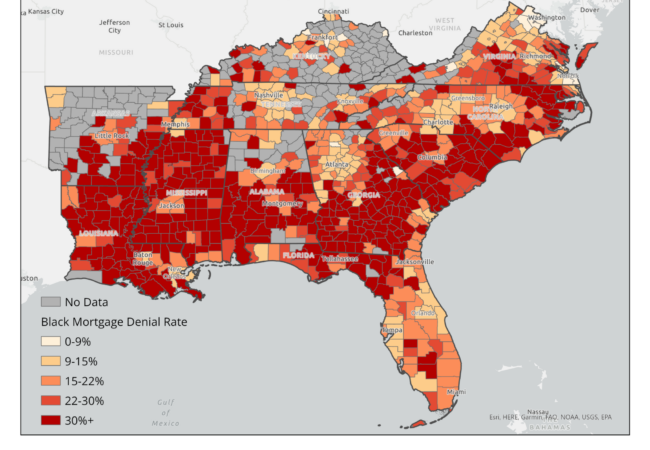

Redlining and other forms of housing segregation officially ended in 1968 with the Fair Housing Act, but access to lending still differs depending on a person’s race. People of color are still more likely to be denied access to mortgage lending than white people. Homeownership is the most common pathway to building generational wealth in the United States and limiting access to capital for buying a home not only prevents people from healthy, safe, and affordable housing and inhibits social mobility.

This month’s map tracks disparities in mortgage lending throughout the Southeast using data collected from federally- backed lenders as part of the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA). It shows the mortgage denial rate by race among counties in the Southeast between 2018 and 2022. As housing costs and high- interest rates raised monthly mortgage payments, lenders denied around 12 percent of home purchase mortgage applications in the Southeast. However, the applicants are not denied evenly. Between 2018 and 2022, about 10 percent of non-Hispanic white applicants, 8 percent of Asian applicants, 14 percent of Hispanic applicants, and 21 percent of Black applicants in the Southeast were denied mortgage loans.

In 2022, the most common reason for mortgage application denials was insufficient income. Income also varies by race. The median non-Hispanic, white household income in 2022 was $81,000; Asian household income was $109,000, Hispanic household income was $63,000, and Black household income was $53,000. Inequities in income, lending, and the ability to build wealth impact a household’s ability to access safe and healthy housing. A lack of mortgage capital also makes it difficult for people to access the benefits energy efficiency, whether through housing choice or home retrofits. Stay tuned for a forthcoming map on lending for home improvements, which will shed light on the ability of households to achieve energy efficiency savings through home improvement capital.

Map of the Month – September

Grace Parker

Map: Southeast Energy Efficiency Alliance

Map: Southeast Energy Efficiency Alliance

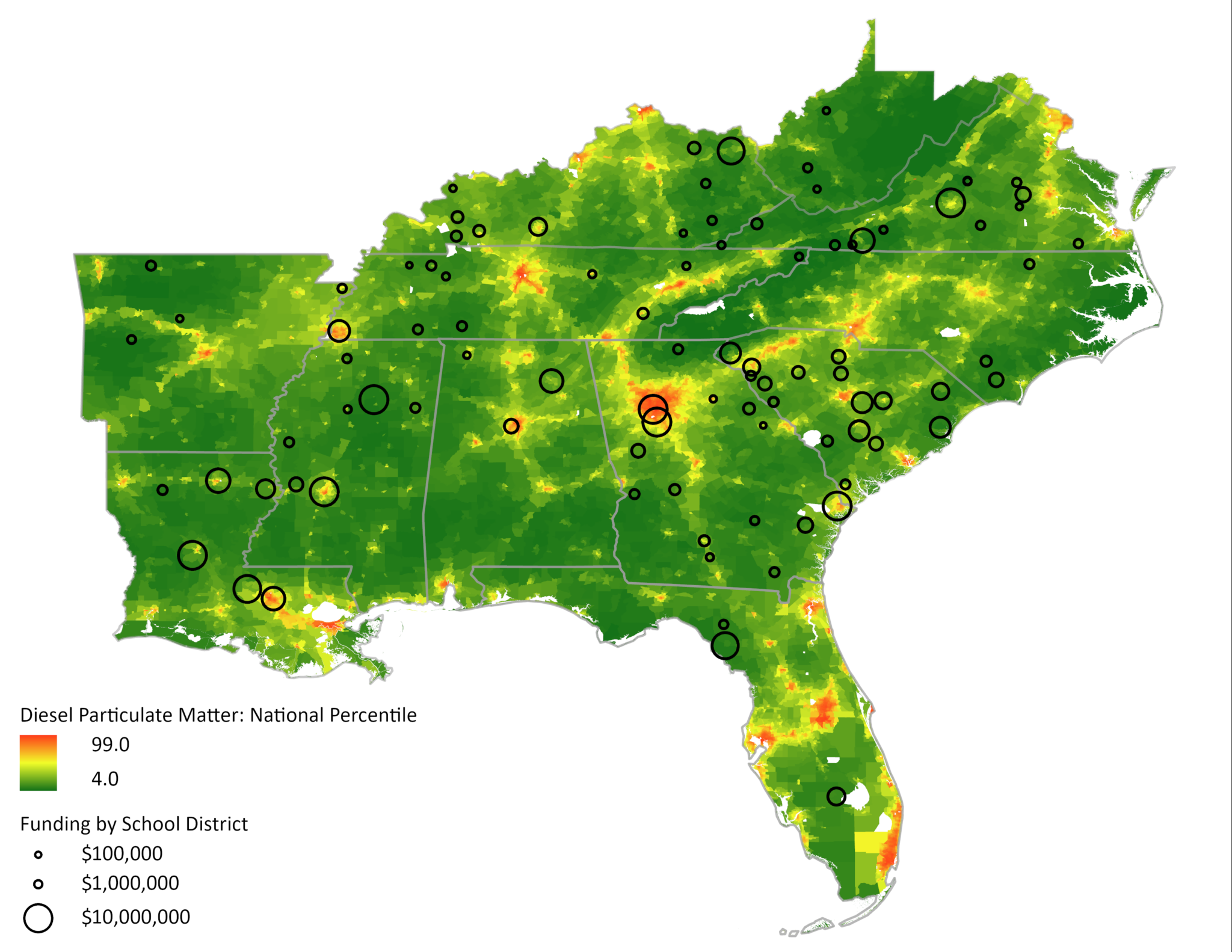

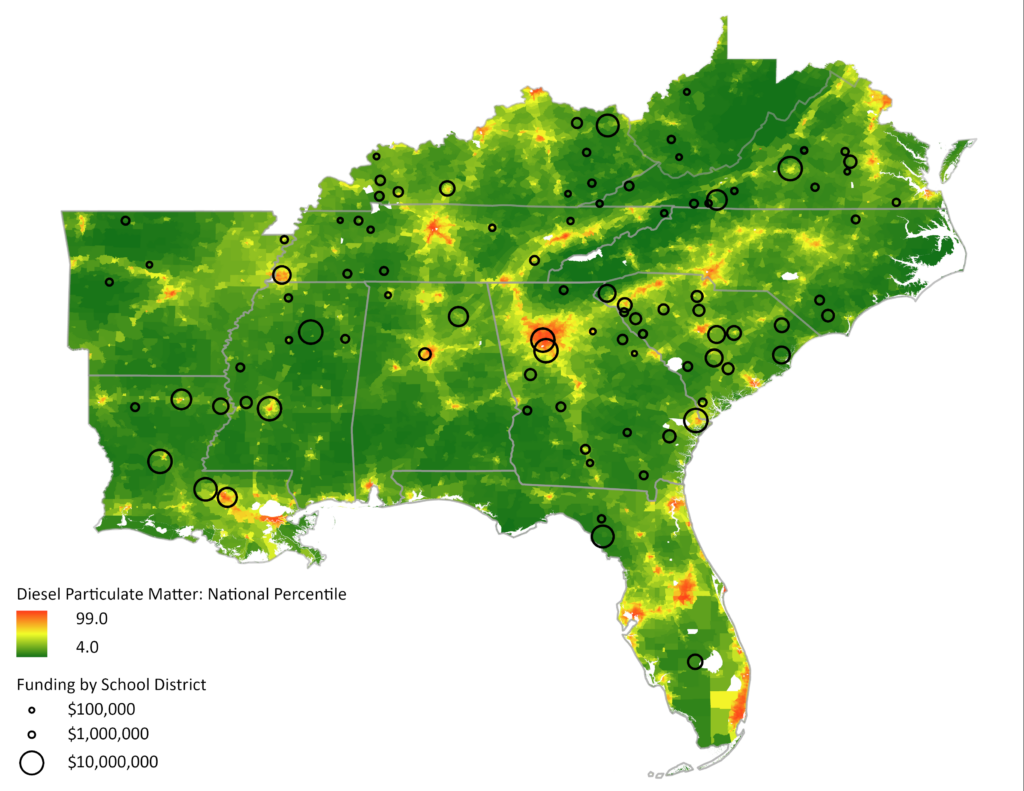

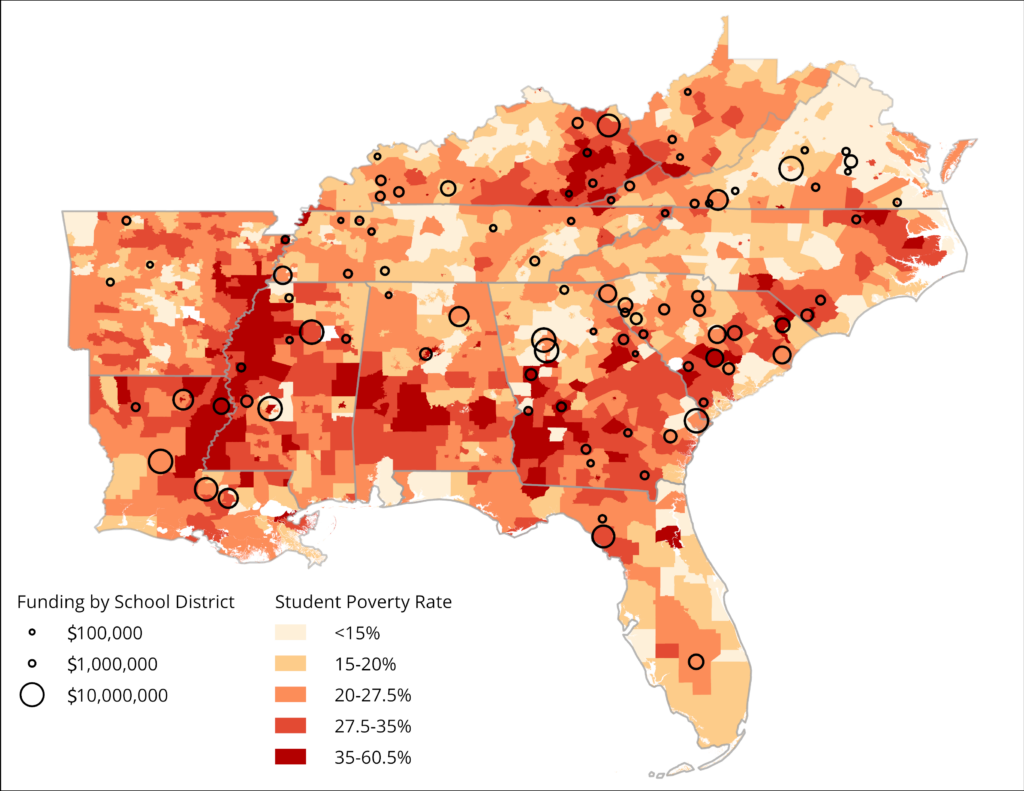

The EPA’s Clean School Bus Program aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and exposure to air pollution by replacing older school buses with low-emission and zero-emission models. Has that funding reached the communities most impacted by the harmful effects of diesel school buses? Diesel buses produce diesel particulate, which has been linked to an increased risk of asthma and cancer. A part of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the Clean School Bus Program provides funding to school districts to purchase new low-emission and zero-emission buses. This funding supports a global reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, local air quality improvements, and health benefits to nearby communities.

This month’s maps show that the school districts that were awarded program funding in 2023 are generally more rural, have high student poverty rates and lower levels of diesel particulate, especially compared to more urban districts. The EPA prioritizes funding for rural school districts, high-need local education agencies, and schools that serve residents of Native American lands. High-need local education agencies include districts where 20 percent or more of students served are from low-income families. The student poverty map shows that most of the funding went to these districts. The Clean School Bus Program largely supports schools that have smaller budgets and serve students from lower-income communities.

This month’s maps reveal a tension between funding districts that have the most difficulty paying for clean school buses and funding districts with the highest diesel particulate pollution. However, we can target funding to areas that need support to overcome both of these challenges, like New Orleans. Although a district with similar needs in Birmingham received a $3.6 million grant, New Orleans districts did not. School districts seeking cleaner air and better health for their communities need additional outreach and technical assistance to support their funding applications to the Clean School Bus Program. By focusing on districts that face multiple obstacles to their achieving their goals, we can deepen the impact of this historic and critical funding.

Map of the Month – January

William D. Bryan, Ph.D. & Joy Ward

We are excited to introduce a new addition to SEEA’s blog this year – the Map of the Month. Every month, our research team will share a map that explores energy efficiency in the Southeast.

Map: Southeast Energy Efficiency Alliance.

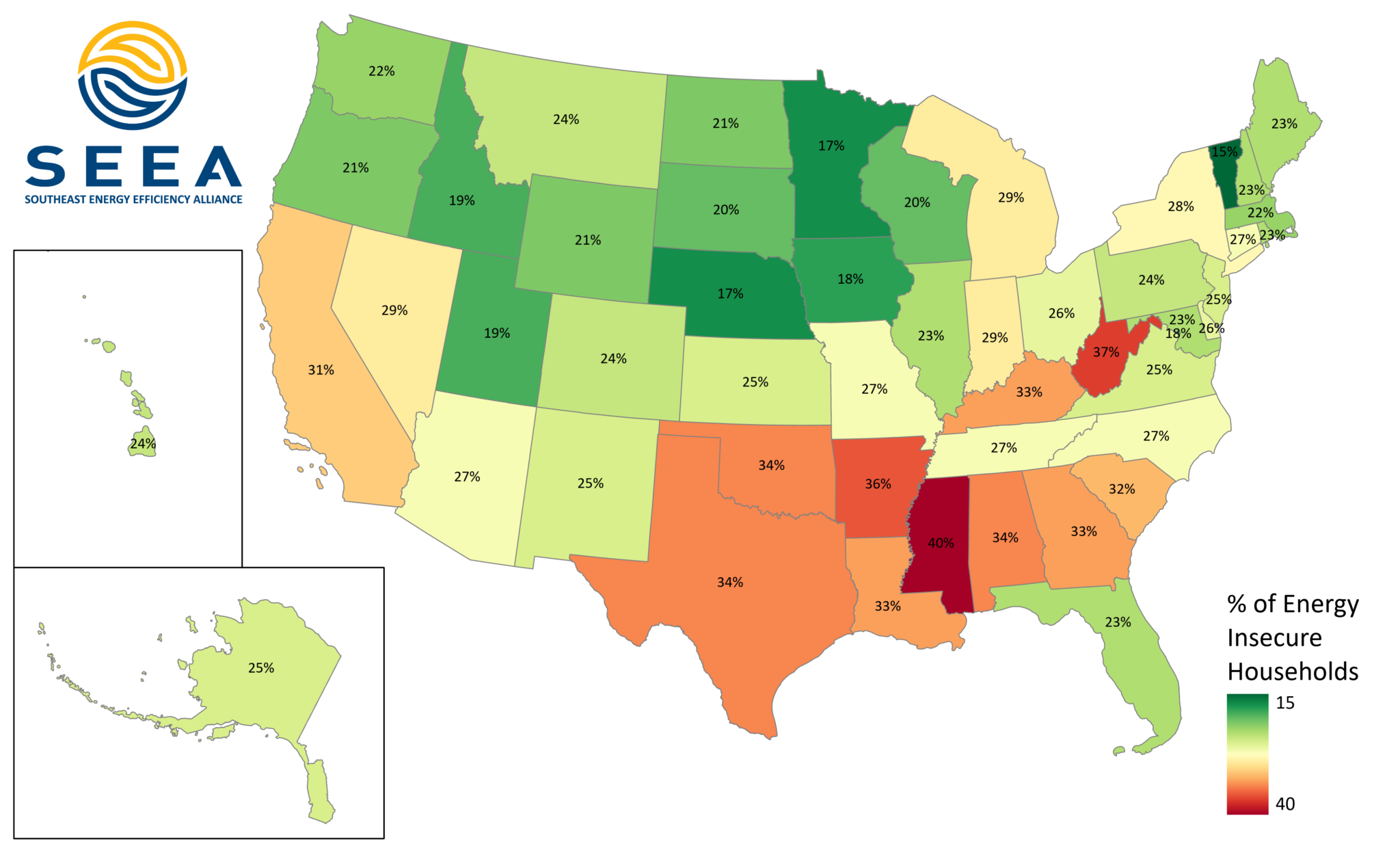

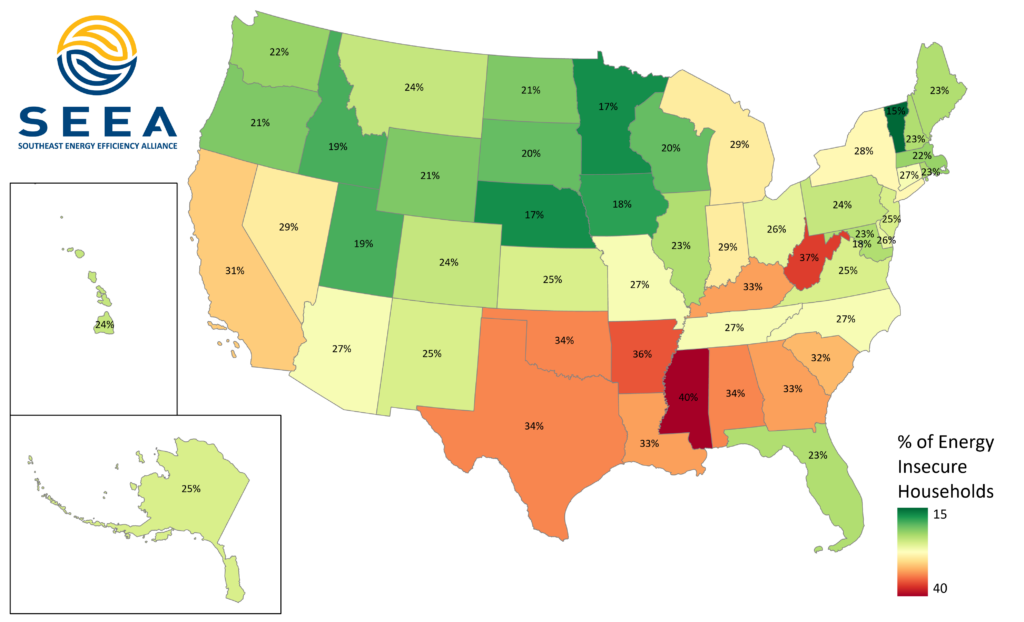

Millions of people in the South who struggle to pay their electric and gas bills every month are threatened with energy insecurity, or when a household cannot maintain vital energy services like heating and cooling. Energy insecurity undermines the health, safety and affordability of housing. The COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated this crisis.

Using new state-level data from the Energy Information Administration’s 2020 Residential Energy Consumption Survey (RECS), this map shows that people living in the Southeast experience the highest rate of energy insecurity in the country. In Mississippi, where 2 out of 5 households struggle to keep on the lights and heat, people are more likely to be energy insecure than anywhere else in the U.S. Of the 9.3 million energy insecure homes in the Southeast, nearly one-third are in Florida and Georgia. People experiencing energy insecurity are at greater risk for respiratory illness, poverty, and being unable to survive or recover in the face of extreme weather.

Beginning with a report and StoryMap, published in 2021, our research team has led SEEA’s work in identifying the historical and current systemic issues that contribute to energy insecurity in the Southeast. In 2022, SEEA announced the Southeast Energy Insecurity Project and continues to advance energy efficiency as a mitigation tool to help people in the Southeast live in healthier, more comfortable homes. You can hear more about how to reduce energy insecurity in our upcoming webinar, Promoting Knowledge and Engagement – Addressing Energy Insecurity in the Gullah Community on Wednesday, Jan. 25 at 11 a.m. ET.

Southeast Energy Efficiency Alliance Announces Inaugural Energy Insecurity Project Implementation Awards

ATLANTA, GA – The Southeast Energy Efficiency Alliance (SEEA) today announced the winners of the inaugural Southeast Energy Insecurity Project Implementation Awards. The award winners were selected by the Southeast Energy Insecurity Project (SEIP) Leadership Forum. The project was formerly housed at Duke University’s Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions.

Sabrina Cowden, principal at Sabrina Cowden Consulting and a member of the Leadership Forum, said, “The award winners are doing the hard work of developing and implementing programs that facilitate better access to energy assistance. We are excited to support projects that provide meaningful pathways to address energy insecurity and can be held up as program models throughout the Southeast.” The awards are as follows:

The City of Savannah (GA) Office of Sustainability & the Athens-Clarke County (GA) Unified Government Sustainability Office

These governments were selected for a shared $10,000 award to support a project that will expand access to Georgia Power’s Home Energy Efficiency Assistance Program (HEEAP), an energy efficiency assistance program for income-qualified customers. This project will promote and explain the HEEAP to the community. The project team will also collect data on observed barriers to participation. This data will be brought to the Georgia Public Service Commission’s Demand Side Management Working Group, which advises both the commission and Georgia Power on existing and future energy efficiency programs, with the goal of lowering participation barriers for Georgia Power customers.

Alicia Brown, the clean energy program manager for the City of Savannah said, “I’m very excited for the opportunity partner with my friends in Athens-Clarke County. There are energy efficiency programs available today, that customers pay for on every power bill, that are not used as much as they should be simply because people don’t know they exist. Our goal is to spend the next four months changing that narrative in our respective communities and collecting insights to take back to the Public Service Commission to make these programs even more effective for those who need the assistance most.”

The Sustainability Institute (Charleston, SC)

This organization was selected to receive a $12,500 award to support a project that will identify and address health and safety challenges that prevent access to energy assistance and launch an awareness campaign to educate energy insecure communities and decision-makers. This project is focused on four underserved communities in North Charleston, SC that have a high number of aging homes and high energy burdens. This project will help develop a program that identifies homes that need repairs before they can receive weatherization upgrades. Project partners and AmeriCorps staff will support raising community awareness and outreach.

The Sustainability Institute’s project partners include the Lowcountry Alliance for Model Communities (LAMC), Liberty Hill Improvement Council, Charleston Area Affordable Housing Coalition, Charleston County Government, Charleston Climate Coalition, and the South Carolina Energy Justice Roundtable.

Bryan Cordell, executive director of the Sustainability Institute, said, “So many families in our region are not only spending more than they can afford to heat and cool their homes, they are also facing home health and safety challenges that prevent efficiency repairs from ever being implemented. We are excited for the opportunity to work with underserved communities to better understand the challenges families are facing so that we can build a programmatic model that holistically addresses those needs. We believe that weatherizing homes is critically important work. The optimal outcome pairs energy upgrades with a healthy and safe living environment and also engages and empowers families.”

##

Questions? Contact Sarah Burgher, senior marketing and communications manager.

Southeast Energy Efficiency Alliance and Partners Named Recipients of Drawdown Georgia’s Climate Solutions & Equity Grant

The Southeast Energy Efficiency Alliance (SEEA), alongside partners Gwinnett Housing Corporation and the Georgia Hispanic Construction Association have been awarded a Drawdown Georgia Climate Solutions & Equity Grant to support the creation of a comprehensive federal investment and workforce development plan to benefit disadvantaged communities in Georgia State House District 98 – the most diverse and under-resourced part of Gwinnett County.

The funding partners that made the inaugural grant round possible include the R. Howard Dobbs, Jr. Foundation and its Dobbs Fund, The Wilbur & Hilda Glenn Family Foundation, The Kendeda Fund, the Ray C. Anderson Foundation, and The Sapelo Foundation.

We are proud to be included among the distinguished grant recipients!

Southeast Energy Efficiency Alliance Announces Southeast Energy Insecurity Project

ATLANTA, GA – Today, the Southeast Energy Efficiency Alliance (SEEA) announces the Southeast Energy Insecurity Project. In April 2022, SEEA assumed leadership of the Southeast Energy Insecurity Project, formerly known as the Southeast Energy Insecurity Stakeholder Initiative led by the Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions at Duke University. The initiative produced a report, Stakeholder Recommendations for Reducing Energy Insecurity in the Southeast United States, which includes 24 recommendations to address energy insecurity in the region.

In the next phase of this work, we are seeking candidates for a Southeast Energy Insecurity Project Leadership Forum and offering Southeast Energy Insecurity Project Implementation Awards to organizations that seek to advance one or more of the report’s recommendations through tangible action.

Southeast Energy Insecurity Project Leadership Forum

SEEA is seeking candidates for a Southeast Energy Insecurity Leadership Forum to review applications for the Southeast Energy Insecurity Project Implementation Awards and to contribute to a webinar series for interested stakeholders to discuss other recommendations and topics related to energy insecurity in the region. Candidates are asked to complete an online application at bit.ly/SELeadershipForum.

Southeast Energy Insecurity Project Implementation Awards

SEEA anticipates funding up to 1-2 proposals ranging from $10,000 – $15,000 through this RFP. Projects must be located within SEEA’s 11-state region including: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia and West Virginia. Submissions are due no later than Friday, September 2, 2022. Winners will be announced at the Southeast Energy Summit, October 2-5, 2022 in Atlanta, GA. Learn more about the awards at www.seealliance.org/rfp.

An informational webinar for more information on the leadership forum and awards is scheduled on Tuesday, August 9, 2022 at 10 a.m. ET. Registration is available at www.seealliance.org/events.

Questions? Contact Sarah Burgher, senior marketing and communications manager.

Our top blog posts of 2021

In 2021, the covid-19 pandemic continued to influence our desire to improve the safety and efficiency of our indoor spaces and we saw an increased public and private investment in energy-efficient technology, manufacturing, and policy. SEEA welcomed a new president, and we expanded and deepened our commitment to equity within our industry. In this notable year, these are the blog posts that you read, shared, and liked the most.

1. What is energy security versus energy burden?

Originally published March 15, 2021

Last month, SEEA released our report, Energy Insecurity Fundamentals for the South. We believe using common metrics is essential to creating robust and prescriptive policies that address the multiple dimensions of energy insecurity. […]

2. Going beyond recovery with the American Jobs Plan

Originally published April 22, 2021

For patients recovering from a major illness or trauma, doctors stress the importance of improving social wellness as a part of recovery. They prescribe getting back on your feet as the first step, but note that staying healthy requires a long-term investment in one’s physical, mental, and social health. […]

3. Energy efficiency for all – the opportunity ahead

Originally published May 6, 2021

While I officially started working at SEEA on April 26, I have had the pleasure of working with SEEA staff and board members for more than ten years. The team’s dedication to realizing a more energy efficient Southeast that benefits all people has long inspired my curiosity […]

4. How American Efficient is realizing a more diverse energy industry

Originally published November 10, 2021

The American Efficient DEI Action Team

Over the last year, a team at American Efficient developed a Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) action plan to put some of our company’s values into practice. As a group of mostly white people in a mostly white company—and industry—we regard this as a privilege, in all senses of the word. […]

4. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act will transform the Southeast

Originally published November 12, 2021

On Friday, November 5, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. The bill passed the Senate in a bipartisan vote in August and President Biden is expected to sign the bill on Monday, November 15. The $1.2 trillion package is a historic investment in infrastructure that advances energy efficiency, resiliency, and electric transportation. Combined with the President’s Build Back Framework, it will average 1.5 million additional jobs every year for the next 10 years. […]

How heat islands worsen energy inefficiency and inequality in our cities

Just after 6 p.m. on Saturday evening in August, policy manager, Claudette Ayanaba and I met at the Outdoor Activity Center in southwest Atlanta to volunteer with the Atlanta Heat Watch Campaign, led by Spelman College professors, Dr. Guanyu Huang and Dr. Na’Taki Osborne Jelks. The campaign uses volunteers to measure temperatures in various neighborhoods at different intervals and aims “to document how heat risk aligns with other important dimensions of population vulnerability to climate change, including race and ethnicity, income, access to air conditioning in the home, population comorbidities for heat illness, and public investment to-date in climate adaptation.”

Dr. Huang handed us a sensor made of white PVC pipe used to measure heat. He then pulled out his phone and texted me a link to the map of our route, which looked like a large puzzle piece outlining Midtown Atlanta. Volunteers measure temperatures along three routes: one south of downtown, one around Emory and Decatur, and the one we were assigned to, through Midtown and Inman Park. The intent was to evaluate how heat might differ in neighborhoods with different characteristics.

Claudette agreed to drive, and I called out the turns. We got in the car, and she set the GPS for Daddy D’z BBQ, our starting point just east of Downtown. As we started our route around 7 p.m., I noticed some nearby restaurant diners looking at the nearly two-foot-long arm of the heat sensor clipped to the window and sticking out over the car roof, likely questioning what we were doing.

It was a good question. Weeks before, Claudette and I both received emails inviting us to volunteer for the campaign. A few years ago, I might have skipped over this email, but recently SEEA has been researching and evaluating the influences on the access and affordability of energy, or energy insecurity. In 2020, we worked with the Texas Energy Poverty Research Institute (TEPRI) to create a StoryMap that illustrates the long-term and compounding energy impacts of discriminatory policy and racism on communities of color. The research draws a through line between historic racist housing policy and the high amount of inefficient housing in low-income communities today.

A family living in an inefficient home is hit with a double whammy if they live in a heat island, making it significantly more difficult and more expensive to cool their home in the summer. A heat island is an urban area that experiences higher temperatures than surrounding areas. Higher concentrations of emissions from traffic corridors, closely situated buildings, and a lack of green infrastructure can all contribute to a local 1 – 7 degree temperature increase. Heat islands can occur under various conditions, in small or large cities, in the suburbs, in different climates and seasons, and during the day or the night. However, for people in low-income communities, heat islands are an additional barrier to maintaining healthy and comfortable homes. Heat related deaths are the number one weather related cause of death, and low-income communities and communities of color experience it at much higher rates than affluent, predominantly white neighborhoods. Low owner-occupancy rates in historically segregated communities also means that residents typically have less control and fewer resources to improve the efficiency of their homes. In response to these realizations, Miami Dade County in Florida just appointed its first Chief Heat Officer to develop solutions for residents in anticipation of mounting negative impacts of rising heat on residents and other communities are expected to follow suit.

Energy efficiency is a powerful tool for mitigating the heat island effect and increasing temperatures due to climate change. Weatherization improvements like better insulation, sealing gaps in your attic or crawlspace, and advanced building technologies like smart thermostats and heat pump water heaters can lower energy bills and reduce the risk of heat-related illness in homes. An energy-efficient home holds its temperature more evenly and requires less energy and less money to heat or cool. Many electric utilities in the Southeast offer energy efficiency programs that connect customers with services, products, and rebates to improve energy efficiency. However there continue to be gaps in residents’ ability to access these resources. For two years, SEEA has been working with partners including the City of Atlanta and Georgia Power to identify energy efficiency solutions for homeowners, landlords, and renters in the six most energy-burdened ZIP codes in Atlanta. We’re learning about the specific challenges and needs faced in each area and designing solutions that provide residents more access to energy efficiency resources that could significantly improve their lives.

It was our understanding of all the compounding energy challenges facing Atlanta residents that led us to spend a couple hours on a Saturday evening driving around the city volunteering with the Atlanta Heat Watch Campaign. In that time, we noticed that most of our route was through tree-lined, more affluent neighborhoods. The streets included on our route were far greener than the roads we had travelled to Outdoor Activity Center, and in a few months we will learn about what impact that had on the temperature in each of those neighborhoods. While we did not gather any information on what people were experiencing inside their homes that evening, my experience tells me they likely used less energy than similarly sized homes in neighborhoods with fewer trees and green space. We look forward to learning more about the story the data tells and will provide updates to this blog post.

Additional Resources:

- Climate change is making the whole city hotter—but rising temps may put some Atlantans in more danger than others, Atlanta Magazine

- ‘Hotlanta’ is even more sweltering in these neighborhoods due to a racist 20th-century policy, CNN

- Tips on managing summer heat, UrbanHeatAtl & Spelman College students